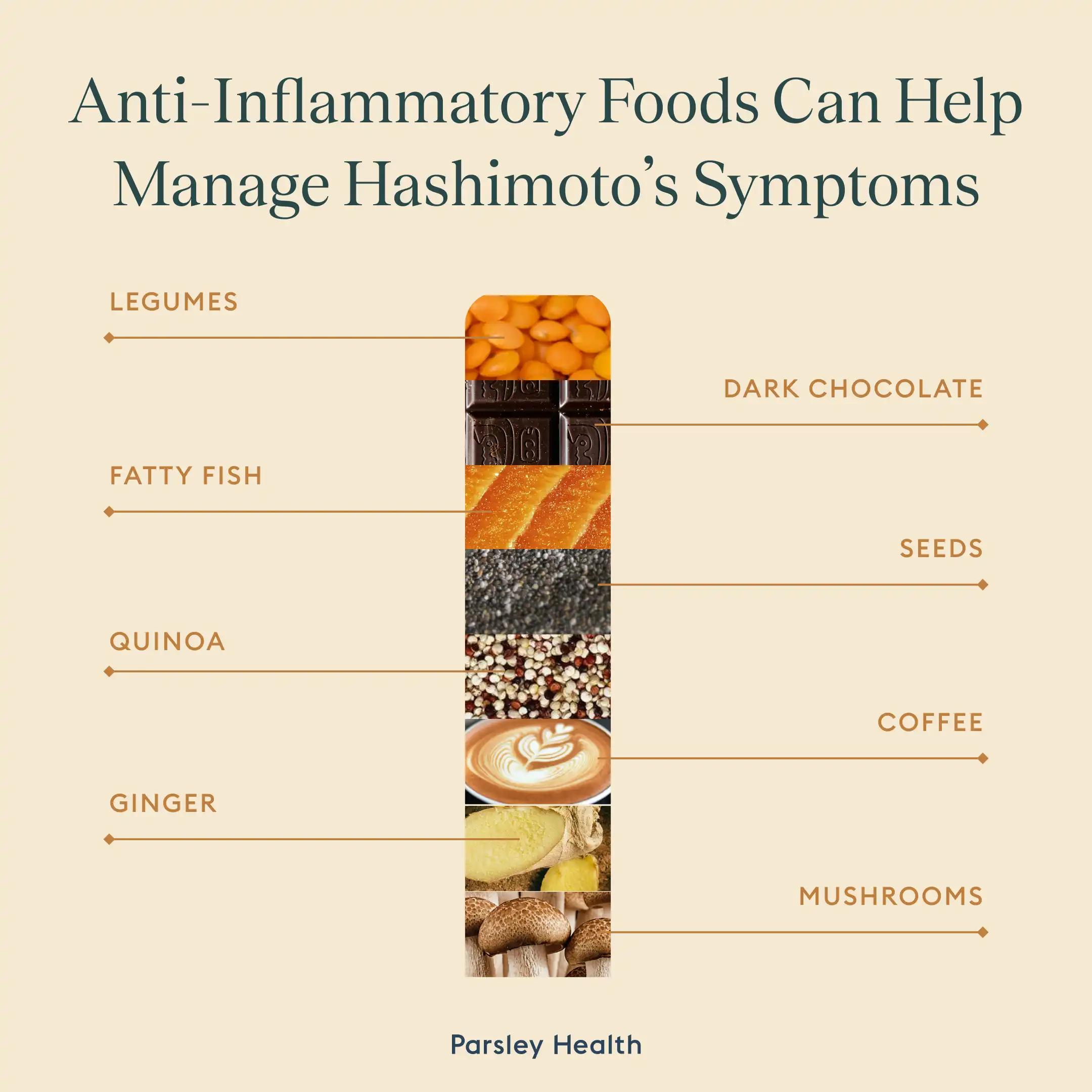

Hashimoto’s thyroiditis is an autoimmune condition affecting the thyroid gland, which is located at the base of the neck. Hashimoto’s can lead to hypothyroidism, an underactive thyroid, which can lead to frustrating and even life-threatening symptoms if left untreated. Although not a cure for Hashimoto’s, a Hashimoto’s diet may help reduce your symptoms and improve your quality of life. Hashimoto’s diets combat inflammation and support gut health.

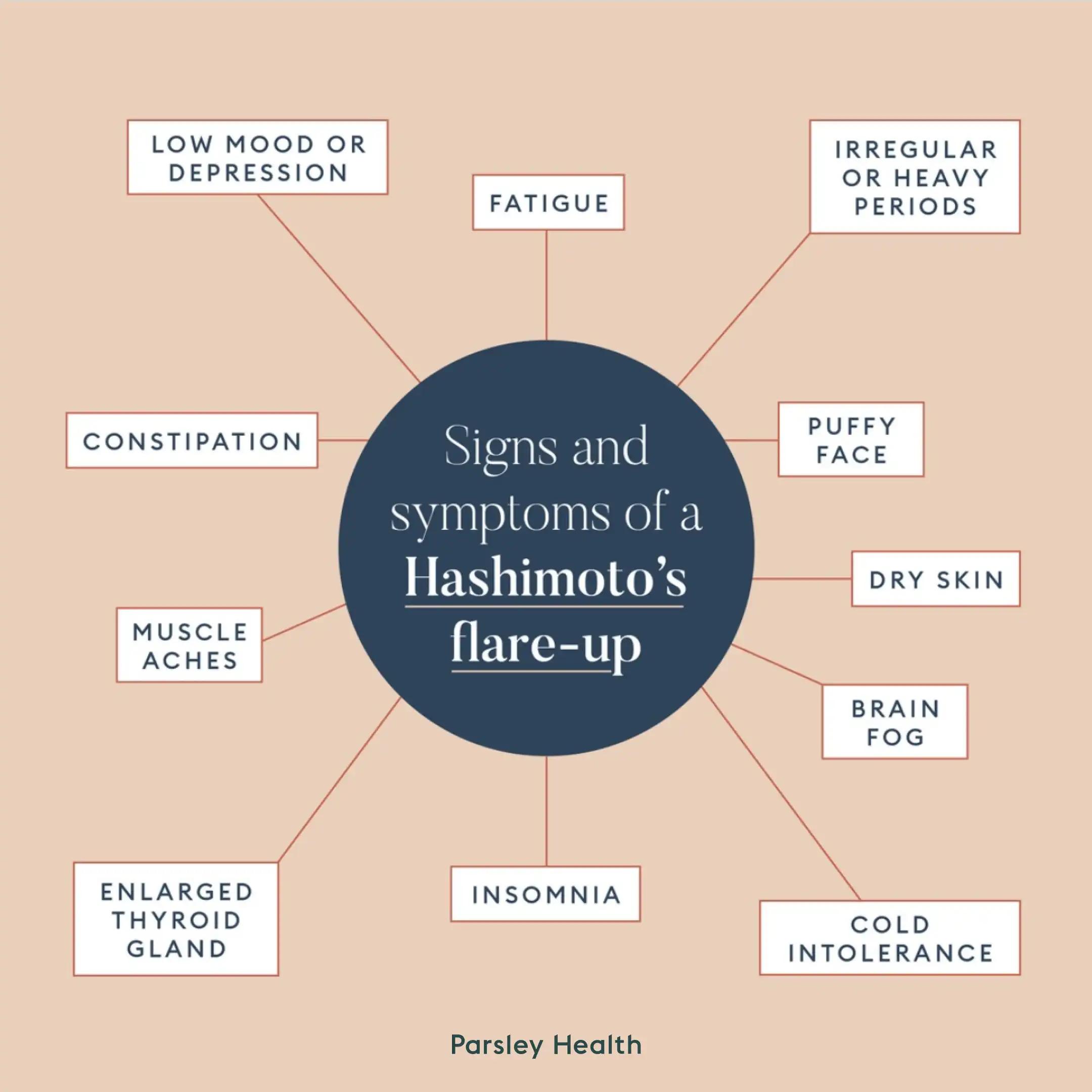

From fatigue to weight gain to depression, Hashimoto’s thyroiditis can cause several frustrating symptoms. If you have this autoimmune condition, you may be looking for ways to mitigate the effects on your quality of life. Diet can help.

Several dietary modifications may help slow or prevent the progression of the disease and the development of comorbidities, conditions that occur alongside another. In the case of Hashimoto’s, comorbidities include obesity, hypercholesterolemia (high cholesterol), and type 2 diabetes.

You may have heard of the Hashimoto’s diet. It’s not a single diet protocol, but rather a dietary philosophy that harnesses the power of nutrition, alongside other treatments, including medication, to help manage Hashimoto’s, which affects the thyroid gland.

“Targeted nutrition helps stabilize energy, reduce antibody levels, and address common co-issues like gut permeability, nutrient deficiencies, and blood sugar imbalances,” says Jennifer Habashy, NMD, a naturopathic doctor and assistant medical director at Claya.

In this article, we’ll explore what Hashimoto's is, dietary changes that may help, what foods might be best to reduce or avoid, supplements that may support your health, and more.

Understanding Hashimoto’s disease

The thyroid is an endocrine gland located at your neck’s base. It’s responsible for secreting crucial hormones that help your organs and tissues perform their daily functions. This butter-fly shaped gland also helps manage metabolism and growth.

In the United States, Hashimoto’s is the most common cause of hypothyroidism, an underactive thyroid, meaning the gland isn’t producing adequate hormone amounts of the inactive thyroxine (T4) and the active triiodothyronine (T3). Consequently, the pituitary gland steps in and produces more thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) to make your thyroid work harder.

If you have Hashimoto’s, your body attacks or destroys thyroid cells, leading to fibrosis or scarring. The prevalence of the condition in the United States ranges from 5 percent to 20 percent, with more people assigned female at birth affected than those assigned male.

To diagnose Hashimoto’s, a clinician may test your thyroid-related hormone levels and for certain antibodies (immune system proteins) related to thyroid antigens, which cause your body to develop a specific immune response. Research is ongoing as to the underlying causes of Hashimoto’s, but likely a combination of genetic and environmental factors—such as lifestyle, nutrition status, and more, play a role.